Blog Post

Micro Bit giveaway

Mar 22, 2016 07:55 by Nadia Bezhan

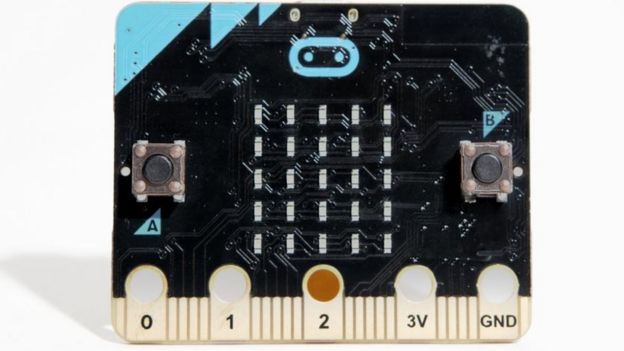

It was last May that the BBC unveiled an ambitious plan to give a million schoolchildren a tiny device designed to inspire them to get coding. Now, after a few bumps in the road, the Micro Bits are finally ending up in the hands of children.

The tiny device can be plugged into a computer and programmed to do all sorts of cool stuff, and Year Seven pupils across the UK are being told it is theirs to take home.

Some, who have had early access to the Micro Bit, have come up with amazing projects - like the Yorkshire school that sent one up 32km (20 miles) on a balloon bringing back pictures of its journey to the fringes of space.

But, amid all the excitement from the young people getting a new toy, this is where the serious stuff starts. Big claims have been made for how this project can change the way children learn about and engage with technology. Now, it's up to teachers to make that happen.

I've been talking to two people with different perspectives on the Micro Bit. Steve Hodges is a Microsoft engineer who was closely involved in the design of the device and Drew Buddie is head of computing at a girls' school and chairman of NAACE, an educational technology association.

Steve told me that his whole career in computing had started as a result of the BBC Micro in the 1980s.

"I begged my parents to buy me one for home. I told them I would never ask for anything again if they bought me a BBC Micro!" he recalls.

His hope is that the Micro Bit will prove similarly inspiring.

Unlike his generation, today's children already have access to a variety of computers, so the aims are different.

"We built a small, low-power 'embedded' device, which actually needs a regular computer to program it. In a world of wearable devices, connected gadgets and the 'internet of things' the Micro Bit is both relevant and yet unusual - just like the BBC Micro was 35 years ago," he says.

Drew is very enthusiastic about the aims of the Micro Bit, and he too harks back to his childhood.

"For those of us who were around for the BBC Micro, we feel that we are on the very cusp of a renaissance of that era," he says.

But the repeated delays in rolling out the device to schools have dismayed him.

Teachers have had Micro Bits for some weeks but they are being delivered to children just as the term ends.

"There seems to be a perception at the BBC that teachers were ready to drop everything to use these devices as soon as they became available," Drew says. He explains that it's now too late in the year for many to adapt their lesson plans.

The delays are understandable - bringing together a consortium of companies to produce something that had to be exciting, educational and safe was always going to be a challenge. One difficulty came when the team realised that the small watch battery in the original version could be a choke hazard for small brothers and sisters when the device was taken home.

"The real challenge was the scale of the project," says Steve Hodges.

Usually a company will start out making a few thousand of a new device.

"But we knew that we would be manufacturing one million devices from day one so we needed to plan for every eventuality we could think of to make the device as feature-rich, safe and robust as we could," he explains.

I asked Steve whether it might not have been better to give children a Raspberry Pi, the barebones computer that has already been a big hit.

He sees the two devices being used in tandem but says the Micro Bit is designed to be different, and to attract "students who enjoy a more hands-on, tactile learning style and who would otherwise find coding less appealing".

One key feature of the Micro Bits is that they belong not to the schools or the teachers but to the children. It seems, however, that some teachers don't buy into that idea.

Drew says significant numbers "seem to be suggesting that they will try to hold on to the devices in schools by discouraging the students from taking them home".

But he says that won't happen at his school.

"My attitude is that I'm going to give them to the girls because they belong to them," he states.

He remains enthusiastic about starting some projects and thinks his students will be keen to use their Micro Bits to make some wearable technology. But he says some of the early impetus has been lost and, rather than being incorporated into lessons, the Micro Bit will be taught in lunchtimes and after-school clubs.

The BBC project is focused on schoolchildren who entered Year 7 last September. There is still time for them to get inspired, but it now looks as though it will be in Year 8 that they may really get to grips with their Micro Bits and learn most from them.

So, what happens to those who enter Year 7 this coming September?

There is talk of turning the Micro Bit into a commercial product and, given the level of interest in it, that must be a distinct possibility. Then schools would have to decide whether to buy more of the devices.

The BBC Micro made a big impact in schools and beyond throughout the 1980s, inspiring a generation of computing and gaming entrepreneurs.

It is a big act to follow, but let's hope the Micro Bit can now begin to open a new generation's eyes to the creative potential of computing.